Double Down, Explode, Bridge and Breakout: The innovation options

We can do something about this, however. We can create and demand better definitions and better communication about innovation. To some extent, there have been attempts to create better definitions, or more definitive descriptions of innovation. Take, for example, the concept of defining innovation as incremental or disruptive. These are truly either/or alternatives, but opposite ends of a spectrum of innovation possibilities. On the conservative end of the spectrum you find incremental innovation, which means small changes to an existing product or service, typically within expected confines of a solution or industry. On the other end of the spectrum you'll find radical or disruptive innovation, which means creating something so new and unexpected that it disrupts the existing models or paradigms. Which outcomes are innovation? Well, both are. What's important is understanding the differences in expected outcomes, and the work involved in delivering both.

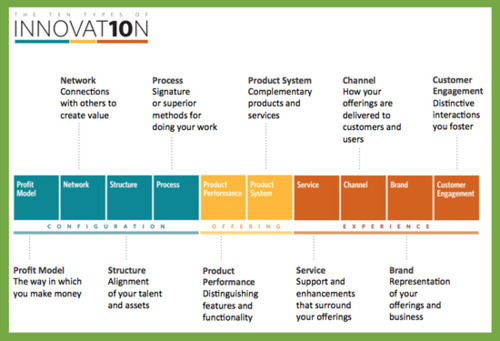

The Ten Types

Far too often, it's assumed that innovation MUST be a new product. Doblin in their work identified ten different types of innovation, starting with products but extending to services, customer experiences, business models, value chains, brands and much more. I've included an image that reflects the ten types Doblin has described, in case you are unfamiliar with the model.

What Doblin was doing by creating this definition was creating more specific language and texture about innovation. In this regard, using Doblin's ten types, we could have an executive say that the innovation they wanted or needed should be an incremental change to a channel, or a disruptive change to a business model. By defining the types, Doblin has expanded our purpose and language, and hopefully created a better understanding and dialog about innovation, the expectations, investments and necessary outcomes. And this is an exceptionally valuable contribution.

Outcomes

But there is at least one more definitional issue that I've frequently stumbled on, and that is the outcome or the intent of an innovation activity. What many executives and managers don't understand is the amount of change that an innovation activity may cause to his or her own business, business model or industry. When these executives ask their teams for innovation, they want the maximum amount of new revenue that can be generated (which means a really interesting and new product, service or business model) but often with the least possible change or disruption to existing business operations (which means incremental change). From our work, we've seen a number of truly innovative ideas that were powerful and valuable simply be rejected because the outcomes were far different than an executive could image. Take for example work we did in the life insurance market. Life insurance is really difficult to innovate, because of the number of competitors and the constraints. Of course, if we can't innovate the product itself we can innovate the channels (online), the experience, the business models and so forth. One idea we had was to use the insights and data collected to add value to other industries - to see aggregated data from decades of experience to other industries that might find value in the data. This idea, which we vetted and found to have value, was so different and so unusual that the insurance firm we worked with stated that they weren't in the data business, even though they manage petabytes of data. The concept of breaking out from offering life insurance and offering valuable data based on years of experience was too confounding. It wasn't an outcome they planned for or expected.

From this work and others we've developed four categories of outcomes, to help inform and distinguish the type and amount of change that's desired. These four categories include:

- Double Down: create incremental change or potential line extensions that work within the existing solutions, business models and frameworks. No idea will be radically different from what the company already does and expects, and none will cause significant change to operating models or expectations. In this case we are doubling down, both on the extent of change to the product or service (small) and to the risk of change of the operations, culture, industry expectations or business model (also small)

- Explode: Explode the business model or industry expectations. This type of innovation is rarely done from within an industry by an incumbent, because they have too much at stake in the existing agreements and definitions of an industry or business model. Exploding an existing model (music distribution on physical media vs digital media) typically occurs from outside an industry rather than within an industry. This option includes huge risk, both in terms of the new product or service, which may be rejected by the customer, as well as the risk to the stability of an industry or convention. That's why this alternative is almost never used by an incumbent in an industry, almost always by an entrant.

- Bridge: create innovations that attack or solve needs or opportunities in a nearby but adjacent market or segment. In this case the ideas are somewhat reasonably anchored in the existing operations but bridge to new opportunities or customers in adjacent spaces. This may cause some change to existing operations and business models, but the change is anticipated and acceptable. This option creates moderate risk both in terms of the new product or service, as well as to the operational capabilities and industry knowledge of the company doing the bridging.

- Breakout: A breakout innovation is one that intentionally causes a team to leave the industry, constraints or business model of the existing corporation, to explore something new. Our example of an insurance company selling its data to other firms could be an example here. This may require a completely new entity or radically change business models and operations.

The new, more definitive language

Using our four category addition, we can communicate far more clearly and concisely about what innovation should do, what should emerge, and what risks or opportunities we are willing to pursue or leave behind. An executive could now ask for a disruptive channel innovation that bridges to a new industry, or an incremental product that merely doubles down on existing investments and does not cause change. But more importantly they can indicate how much change the product or service must create in the marketplace, and how much change the business, its operations and models are willing and able to bear. Many, many corporations want the breakout or bridging type of innovation, but simply are not prepared to make the structural, cultural and business model changes necessary to achieve either. Then, as they become complacent and leave opportunities on the table, they become subject to the "exploding" option - other new entrants or entrepreneurs explode the existing models or bridge into what seemed like a safe and defendable market or segment.

Innovation encompasses all of these "definitions" and many more. When we are inarticulate with our definitions or language, or simply refuse to define what we need and what risks and changes we are willing to bear, we lose opportunities to do more. In the absence of good definition and clear communication, teams will always default to the most conservative understanding of meanings, protecting existing business models, corporate structures, cultures and operational capabilities, which severely limits the potential and range of innovation. Unless and until executives are clear about their goals - not just in terms of profits and revenue but in terms of the amount and type of change they are willing to inflict on their own company and the industry at large - then innovation will be incremental. And that's ok, as long as that was what was intended and what was delivered.

Voted 2nd best innovation blogger two years in a row!

Voted 2nd best innovation blogger two years in a row!