Innovation: the flavor of the month problem

One data point defines an instance, and is difficult to project. Two data points define a line which signals continuity. Three data points begin to suggest a trend. Close to a decade as an innovation consultant constantly confronted with the same challenge suggests a "wicked problem" that needs to be solved. That problem is the flavor of the month problem.

Last week I met with a company interested in building a vibrant, constant innovation capability and culture. The first day I met with the executive team, and they were excited about innovation and its possibilities. They have concerns about investments, tradeoffs and risks, but send clear signals to me that they are "on board" for the investment and the work necessary to build innovation into their operating fabric. On the next day I met their direct reports and deputies.

The senior managers are excellent people. I've had a chance to work with many of them before. As long as innovation was seen as a tool to solve a very real and current problem, they have responded with great alacrity and sponsored innovation activities. Now that we are talking about significant changes to corporate direction, culture and the work associated to change these factors to sustain innovation, the team has become wary. First question: what did the executive team say about this?

No problem, I answer. They are fully behind it. They want more innovation. Next question: what are we going to stop doing, to start doing more innovation? What are the acceptable tradeoffs? And that's the ultimate rub. Innovation as a near term fix to an immediate problem simply introduces a new way of looking at a problem and generates quick solutions, but doesn't change the culture or processes. Everyone likes this kind of momentary scope enlargement and capability development that we call sporadic, occasional innovation. Introducing the idea of innovation as a continuous capability, training people on new tools and techniques, expecting more and more consistent innovation activities with more innovation outputs, that raises eyebrows. Not because of the investment per se, but because of the commitments and tradeoffs necessary.

Flavor of the month

Unfortunately, the phrase "flavor of the month" is not just consultant-speak. In the reports meeting, one of the attendees actually said: how do we know this isn't just the flavor of the month? In other words, does the executive team understand how much work this requires, how much investment in resources and funding, and the amount of time and attention that must be diverted from other things? How do we, the direct reports, know that the executive team won't change their minds, or shift priorities again next month, when a new flavor of the month is presented?

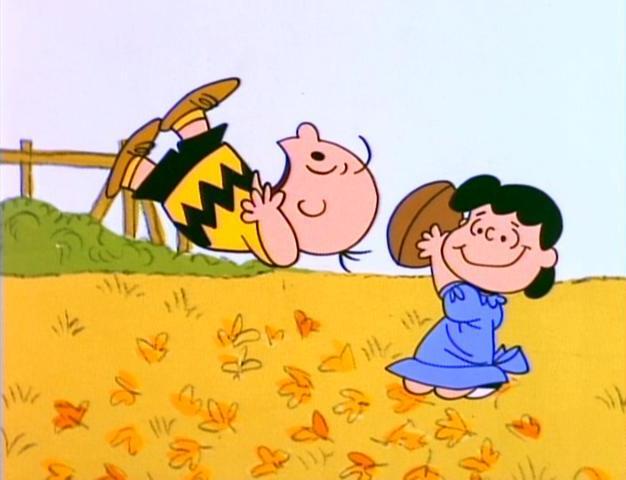

Innovation is an activity that is especially susceptible to flavor of the month thinking, because it is new, unusual, risky and uncertain, and people don't have the basic skills or experience to do it well. That means the learning curve is far greater, and the inertia not to take on this effort is far larger than for other initiatives. No one wants to start working with the assumption that the funding and resource commitments are there to do innovation, only to have the rug pulled out from under them. And boy, have some direct reports played the role of Charlie Brown as Lucy pulls the football away just as he plans to kick it out of the park.

Communication, Commitment, Sustainment Gap

Between executive teams and their direct reports and subsequent management levels there are gaps in understanding, in strategic alignment, and in depth and breadth of commitment. The direct reports want innovation just as much as the executive team, but are far more cautious because they also have direct responsibility for the day to day activities of the business. They are pulled between the desire for innovation and the realization of the amount of work and focus necessary to get day's work done. They cannot afford to start new initiatives that won't be supported or sustained, even initiatives that have high return. The fact that the returns from innovation are undocumented, uncertain and poorly scoped simply compounds the problem, while the fact that the organization lacks skills and faces significant inertia only builds a higher barrier to innovation. There is no gap in desire, only in practical steps to start an innovation activity, build skills, overcome inertia and once that investment is in place, sustain focus long enough to build momentum.

Note that this gap isn't the fault of the direct reports. I place the fault for this gap where it belongs, with the executive team. And there are few executive teams that escape this finger of blame. Executives are supposed to create clear objectives, provide the resources necessary to accomplish the objectives and remove barriers that stymie their teams. If the goals are uncertain, the resources unavailable and cultural and skill barriers remain, that's not the fault of the direct reports. They are simply doing the best with what they have. This gap is a management gap, a commitment gap, an engagement gap.

The difference between cutting and growing

There's a reason that executives have skirted their innovation duties. For years they've asked their teams to do the same with less. While we talk about "more with less' in reality it's usually the same or slightly better outcomes with less resources or inputs. These goals don't require much direction. Cutting is far simpler than growing or innovating. When cutting is your goal, you find the biggest cost driver and reduce it, then the next one and so forth. That's not hard and doesn't require a lot of skill or direction. However, when growth or innovation is your goal, the scope and range of options is almost infinite. Growth in existing customer base or new customers? In existing markets or adjacent markets? With incremental change or dramatically new products? How much growth? How much risk? Many innovators are stymied from the start, because scope, strategy and direction are so poorly defined that every option is valid, and the range of options is simply unlimited.

Anyone can cut, with little direction. Just tell them how much - a 5% or 10% reduction. Few people can innovate, and the range of options and possibilities is dramatically larger than when cutting. Without scope, strategy and good communication, teams struggle to determine which alternatives are valid. And often, by the time they choose a course, the executive team has given up, lost interest or shifted priorities. So, like Charlie Brown, they approach the football Lucy has teed up with great trepidation. And no wonder. That football has been snatched away many times in the past, and mid to senior level managers are nothing if not good learners.

Workmat as a solution

Paul Hobcraft and I developed the Innovation Workmat to attempt to create linkages between the executive team and the rest of the organization, and to create alignment across the executive team. Unless the executive team is aligned and agrees to common language, definition and strategy, and is in full support of innovation as an enabler to strategy, innovation is difficult. Unless the executive team demonstrates patience, engagement and provides resources, their direct reports will providen token innovation efforts while carrying on with business as usual. The Workmat assessment helps identify gaps in linkages, in alignment, in capability and in sustainment. Talk to us if your organization demonstrates the "flavor of the month" problem where innovation is concerned.

Voted 2nd best innovation blogger two years in a row!

Voted 2nd best innovation blogger two years in a row!

1 Comments:

In this example it appears that both executive and senior management view innovation as a "project" that you decide to start and resource. The question of management about what to drop to invest in innovation is indicative of that. If this particular company operates with this project type thinking it is not surprising that it results in 'flavour of the month initiatives'. In the case of innovation as a 'project' with expected return on investment the prognosis is very poor for it turning out anything other than a flavour of the month casualty.

To be successful in innovation, the culture of innovation has to be pervasive and ingrained in every aspect, in every function and in every person starting right at the top. This requires that the leader of the organisation has to have a clear understanding of what innovation is and be able to facilitate a collaborative working environment and employee engagement in which innovation can thrive. It is a rare occasion to see that in a corporate leader. One of our own staff had the good fortune to work in a company with a long-standing innovation culture (Bose) and therefore we usually stress that it is most important that the leader of the organisation and senior executive are willing to put in substantial effort (time and money) themselves into become competent in innovation. This takes time. It is not only about facilitating innovation activities of middle management, functional managers and employees in general, but additionally also learning to understand and ensuring that a culture change towards openness, collaboration and employee engagement is actually happening through leading by example.

Ken Blanchard in his recent blog on employee engagement points out similar thoughts and indicates tht success is usually not automatically guaranteed (http://www.fastcompany.com/3002382/why-trying-manipulate-employee-motivation-always-backfires).

Thank you for your thought provoking article.

Elke Scheurmann

Rapid Invention

http://www.rapidinvention.com/

Post a Comment

<< Home